Biography Of Abd al Aziz Rantisi

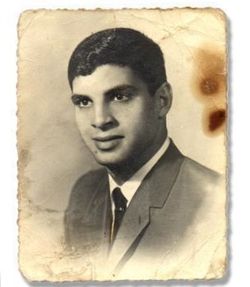

'Abd al-Aziz Rantisi (Abdul Aziz Rantissi). Pediatrician; co-founder and principal spokesman of Hamas. Considered one of the movement's most uncompromising leaders: became Hamas' leader in the Gaza Strip on the assassination of Ahmad Yassin, 22 March 2004. Married with six children; his base is the Shaykh Radwan area of Gaza City. Short biography available here.

Rantisi was born 23 October 1947 in Yibna, a small town between Ashkelon and Jaffa. When he was 6 months old, the family were made refugees from the 1948 war. With 200,000 others, they fled to Gaza (then home to 80,000 people), expecting to return at war's end. Settled in Khan Younis Refugee Camp (second largest refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, at that time under Egyptian rule), where their neighbors were the family of Mohammed Dahlan.

(1998 interview: Q: Have you visited Yibna? A: Yes, and I have seen our house. I found a right-wing family living there. Q: How did that affect you? A: Very strongly. The image of my city, as my parents have told me, my home and my parents' flight with me in their arms does not leave my mind. In general, the issue of forced exile from our homeland has had a profound effect on my thinking).

Grew up in extreme poverty; lived with parents, 8 brothers and 2 sisters in a tent for four years, then in an abandoned school building, before moving into an UNRWA mud house. Started working at age 6 to supplement father's income. An uncle was killed when Israel shelled Khan Younis RC in the Suez crisis of October 1956.

Rantisi attended the UNRWA secondary school in Khan Younis. Graduated top of his class in 1965. Egypt at that time offered university education to exceptional Gaza students who were too poor to pay tuition, and Rantisi began studying pediatric medecine at the University of Alexandria that fall. Professed no political or religious interests at that time, his main interest was in becoming a doctor. At Alexandria, he ran into a familiar face, Sheikh Mahmoud Eid, who had been imam of the mosque in Khan Younis when Rantisi was a child. Eid introduced him to the Muslim Brotherhood, and its belief that native Islam, not Gamal Abdul Nasser's imported, socialist-based pan-Arabism, would solve the problems of the Arab world, a philosophy that caught on with Egyptian students after Nasser's defeat in the 1967 War. Rantisi: "It was because of Mahmoud Eid that I eventually became a faithful follower of the Brothers".

Eid introduced him to the works of two Islamic scholars: Sheikh Hassan Banna, who founded the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 1929 and was its "Supreme Guide" until he was murdered 20 years later, and Sayyid Qutb, a theoretician and writer who was hanged in 1966 for allegedly plotting to assassinate Nasser. Rantisi cites two teachings from Qutb's Signpost on the Road (1964) as influential on him:

1. Only Islam in all the branches of our life, in the home, in the school, in medicine, in engineering, in how to deal with others, can realize the potential of the Arab people. Islam means science and development. It means all the best manners in your life and, above all, values.

2. The communists failed. The nationalist leaders failed. The secularists totally failed. Now the field is empty of all ideologies - except Islam…Now at this most critical time when turmoil and confusion reign, it is the turn of Islam, of the umma to play its role. Islam's time has come.

Rantisi completed his degree and returned to Gaza in 1972; founded the Gaza Islamic Centre in 1973. The Strip was by this time under Israeli occupation: its refugees camps provided thousands of recruits for Fatah and the PFLP, and anarchy ruled on the streets, with PLO activists targeting Israeli soldiers and local Palestinian collaborators. In 1974 he returned to Alexandria for his two-years Masters in Pediatrics. He Formally joined the Muslim Brotherhood on his return to Gaza in 1976. At that time he took up an internship at Nasser Hospital, the main medical facility in Khan Younis RC. (He was dismissed as head of Pediatrics there by the Israelis in 1983). He also joined the Faculty of Science at the Islamic University of Gaza, on its opening in 1978, teaching science, genetics and parasitology there.

The Camp David Accord of 1978 left the Palestinians under Israeli occupation with a toothless automony. Sadat sealed the Egypt/Gaza border, where there had previously been free passage, cutting Gazans off from higher education and employment. In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood opposed the Accords, and Sadat expelled those who were known troublemakers into the sealed-off Gaza Strip. A number of them approached the Israeli administration there in 1978 for licenses to open a jama'ah (Islamic association), to build kindergartens, improve literacy, open stores. The movement began to flourish and branched out into building mosques.

Chief architect of the Islamic revival was Sheikh Ahmad Ismail Yassin (left), a Muslim scholar who did not disguise his belief that Israel was an illegitimate state, but urged his followers not to rush into a jihad before they could win. Instead he urged them to pursue (tarbiyeh) education and (da'wah) preaching. Yassin reviled Arafat and his secular PLO as "pork eaters and wine drinkers". So when he approached the Israeli authorities, as the supreme leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in Gaza, to register charitable organizations to propagate Islam and to recruit supporters for the faith, the Israelis provided the appropriate tax-free licences. They also provided financial support through Brigadier General Yithzak Segev, the military governor of Gaza, who told journalist Graham Usher: "The Israeli government gives me a budget and we extend some financial aid to Islamic groups via Mosques and religious schools, in order to help create a force that can stand up against the leftist forces that support the PLO." According to Segev's memoirs: "There was no doubt that during a certain period the Israeli governments perceived it [Islamic fundamentalism] as a healthy phenomenon that could counter the PLO".

Quote: In the mid-1980's, Israel had a clear policy of letting money come in to build mosques and to build an Islamic infrastructure and give them a kind of laissez-faire environment, a network of libraries, mosques, schools and kindergartens…Although they were aware of the fact that these groups had a radical ideology and at least a potential at some point to start implementing it, they chose a policy of encouraging them in order to counterbalance the PLO which had the opposite policy - a more pragmatic ideology but a conduct of using violence. This was very, very shortsighted. (Ori Nir, Ha'aretz)

Quote: In large part this scourge was self-inflicted, for the Civil Administration has contributed considerably to the development of the Muslim groups that came to the fore soon after the start of the intifada. Just as President Sadat had encouraged the growth of the Islamic Associations to offset the leftist elements in Egypt, many Israeli staff officers believed that the rise of fundamentalism in Gaza could be exploited to weaken the power of the PLO. Sadat's fate was to die at the hands of the same pious zealots he had allowed to flourish. The upshot in Gaza was similar: the Muslim movement turned on the very people who had believed themselves so clever in fostering it. (Schiff & Ya'ari, Intifada, the Palestinian Uprising, New York, Simon & Schuster,1990).

A series of Islamic societies was licensed in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, the most important of which was Yassin's "Islamic Assembly" in Gaza, which had 2,000 members and effectively controlled Gaza's mosques. Within a decade, Yassin built the assembly into a powerful religious, economic and social institution in the Gaza Strip. He developed a welfare network around the mosques, many of which served also as community centres. The number of mosques in the Gaza Strip tripled from 200 to 600 between 1967 and 1987, while the number of worshippers doubled. In the West Bank, the number of mosques went from 400 to 750 in the same period.

An April 1987 classified study by the Israeli govt ("The Gaza Strip Towards the Year 2000", cited in Wallach & Wallach The New Palestinians, pub.Prima Books, 1992) showed how Israel underestimated the Muslim Brotherhood as immediate security risk. Writing just 8 months before the start of the first intifada, General Shayke Erez, then military governor of Gaza, acknowledged there was an escalation in religious fervor in Gaza, and that the Islamists believed in an Islamic state for all Palestine, but concluded that with the exception of Palestinian Islamic Jihad "all the Islamic movements want to focus first on the process of winning the hearts and minds of the Islamic camp and only later begin the active struggle against Israel."

With the Egyptian border sealed, only route out of the Occupied Palestinian Territories after 1967 was via the West Bank and the Abdullah Bridge into Jordan. The Muslim Brotherhood increasingly came into contact with, and under the influence of, Jordan instead of Egypt. They were courted by King Hussein because they were a counterbalance to the PLO. (Palestinian nationalists in the West Bank still tended to see Jordan as the nation that had carved up with Israel the land assigned to the Palestinians in 1947, and saw Jordanian rule as an occupation just as Israeli rule was. Politically they were often as anti-Hussein as they were anti-Israel). The Brotherhood used the money that flowed in from (primarily) Saudi Arabia and now the Jordanian monarchy to build up its network of mosques, cultural organisations and welfare services that were to provide a lifeline to the impoverished Palestinians.

In 1984, Israelis discovered the largest cache of weapons yet uncovered in the Palestinian Territories, in the hands of the Muslim Brotherhood (including some in Yassin's home). The weapons had been bought on the Israeli black market with Jordanian money. The interesting thing from the Israeli perspective was that they had been in the Brotherhood's hands for over a year and not used: they were being saved to fight first against the nationalist PLO, and only then would the masses be recruited to fight Israel. The entire Muslim Brotherhood leadership was jailed for lengthy terms: Yassin got 13 years.

In Yassin's absence, Rantisi stepped up to organise the Muslim bloc in student council elections at the Islamic University, where they won 80% of the vote. In Spring 1986, he launched a bloody (and largely successful) campaign to rid the university of the PLO altogether, carrying out organised attacks on the PLO and purging the school of its supporters. Not all Islamists supported the policy of confrontation with the secular-leftist PLO: in the mid 1980's the al-Jihad al-Islami (Palestinian Islamic Jihad) became active in a different direction. They were opposed the Muslim Brotherhood's priorities, i.e. Islamization of Palestinians before the national liberation struggle. They felt that the Brotherhood was wasting its time fighting for control among Palestinian factions: that the priority was the liberation struggle and that Islamists should follow the example of the PLO's armed resistance, and even coordinate with them. (The first ever PIJ armed attack - in October 86 - was was actually planned jointly by PIJ and the PLO).

With the eruption of the first intifada erupted on 9 December 1987, it was apparent that quietist Islamization first, resistance second, was not a philosophy that appealed to the Palestinian street. On the first day of the intifada, Rantisi and six others (Yassin, 'Abdel Fattah Dukhan, Mohammed Shama', Dr. Ibrahim al-Yazour, Issa al-Najjar and Salah Shehadeh) established an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood to join in resisting the occupation. They named it The Islamic Resistance Movement (Harakat al Mukawwamah al Islamiyya), known by its acronym HAMAS, meaning "zeal". The intention in creating Hamas was to show that the Muslim Brotherhood was one of the initiators of the intifada. (Rantisi: "The decision was to start the intifada under Hamas' name. We were preparing for that for a long time"). Though in fact it was more likely an attempt to catch up with the resisting PIJ and Fatah, to whom the Brotherhood otherwise risked losing the support of its young activists.

The Hamas covenant (i.e. founding charter), published in August 1988, was a blend of nationalism, religion and anti-Semitism. It called for an exclusively Islamic Palestinian state, repudiating the PLO's formulation of a democratic secular state as anti-Islamic, and made territorial nationalism into a religious mission or jihad. It called for the destruction of the state of Israel and equated political Zionism with the Jewish people as a whole, both within Israel and beyond. The charter explicitly rejected direct confrontation with the PLO, but refused to recognise the "sole representative status" of the PLO, positioning itself instead as an alternative leadership of the Palestinian people. To this end, Hamas organised independently of the intifada's unified leadership, issued its own leaflets, and called separate strikes, often on holy days. It intimidated, set fire to and sabotaged shops and businesses that did not respond to its strikes.

Hamas led little action against the Israeli occupation authorities, with the result that Israel did not generally interfere with Hamas-organised strikes, and allowed the flow of funds and movements of emissaries from Jordan to Gaza to go uninterrupted (according to Israeli journalists Schiff and Ya'ari, Intifada: The Inside Story of the Palestinian Uprising). Indeed, Israeli Defence Minister Yitzhak Rabin even had talks with leading Islamists as late as the summer of 1988. But in August 1988, the Israelis discovered evidence of Hamas involvement in terrorism in the northern Gaza Strip. Finally acknowledging that Hamas would not provide a quietist Islamic opposition to the PLO, Israel clamped down, arresting more than 100 Hamas leaders by September.

Rantisi himself had been arrested in January 1988, accused of authoring Hamas' street pamphlets inciting support for the intifada. He was sentenced to 2 ½ years, which he served at Ansar III (Ketziot), Gaza Jail and Kfar Yonnah. He was released on 4 Sept 1990, and effectively led Hamas (with Zahhar) until rearrested for incitement in November 1990. He was sentenced to 12 more months, which he served at Ansar III, first in isolation with Yassin and subsequently in solitary. Released from jail, 12 December 1991. Joined Gaza Medical Association, February 1992. Represented Hamas in the July 1992 reconciliation accord that brought an end to intra-Palestinian infighting in the Gaza Strip. (Haider Abdel Shafi signed for the PLO).

in December 1992, Hamas killed six Israeli soldiers in one week. Israel responded by expelling 416 alleged Islamists to Marj al-Zuhur in south Lebanon, including Rantisi who acted as spokesman for the deportees. (Rantisi: "Marj al-Zuhour was a cornerstone. After that, Hamas emerged as a player in the international arena"). Prior to this incident, the movement had been local and limited. On his return, Rantisi was rearrested by Israel (in December 1993) and held until April 1997.

Relations between Hamas and the PLO deteriorated after the 1991 Gulf War. Hamas took an unequivocal stand against US/Soviet-sponsored peace negotiations and mounted several well-supported actions against the Madrid Conference, including shutting down Gaza with a three-day strike. (Rantisi himself expressed doubt that the Oslo process would amount to anything, on the grounds that Israel would never allow through negotiations genuine Palestinian independence or statehood, only an autonomy that would perpetuate Israeli rule. He therefore opposed any negotiation with Israel). In 1994, Hamas allied with the Popular and Democratic Fronts to form the Damascus-based Palestinian Forces Alliance, an anti-Oslo coalition of 10 opposition groups. In 1993, it participated with these opposition groups in the Birzeit University student elections and defeated the pro-Oslo ticket. One poll at this time indicated that more than 10% of Palestinians in the West Bank and 16% of Gazans considered the Islamic movement their representative instead of the PLO.

Hamas was divided over whether to participate in the first PA elections of January 1996. Sheikh Yassin supported participation because it would "reassert the strength of the Islamist presence", but other members argued that participation would legitimise Oslo. Hamas did not stand in the end, although some Islamists did stand (and win) independently. Hamas indicated that it would stand however in local elections, which probably explains why local government minister Saeb Erekat declined to organize them. Despite sporadic suicide bombings, usually in response to negotiating or security advances by Israel and the PA, by 1997, there were signs that Hamas was returning to its original emphasis on its welfare functions.

In April 1998, Rantisi was arrested by the PA, after calling for the resignation of its leaders (whom he accused of collaborating with Israel in killing a Hamas militant) . He was held in custody without trial, for 20 months, accusing of involvement in the killing of Mohieddin Sharif. He was arrested again in July 2000, after calling the Palestinian participation in the Camp David talks an act of treason, but released in December 2000. Intermittently rearrested, e.g. April 2001, and in December 2001, when after public opposition the PA settled for holding him under house arrest.

Criticised the US for its one-sided support for Israel, and called on Iraqis (Jan 2003) to meet the upcoming "Crusader" invasion with suicide bombings.

Rantisi opposed the June 2003 hudna (one of the Phase One Road map obligations), although Hamas eventually joined it under Yassin's influence. Rantisi subsequently defended the hudna as a means to prevent the US forcing the PA into a civil war with Hamas.

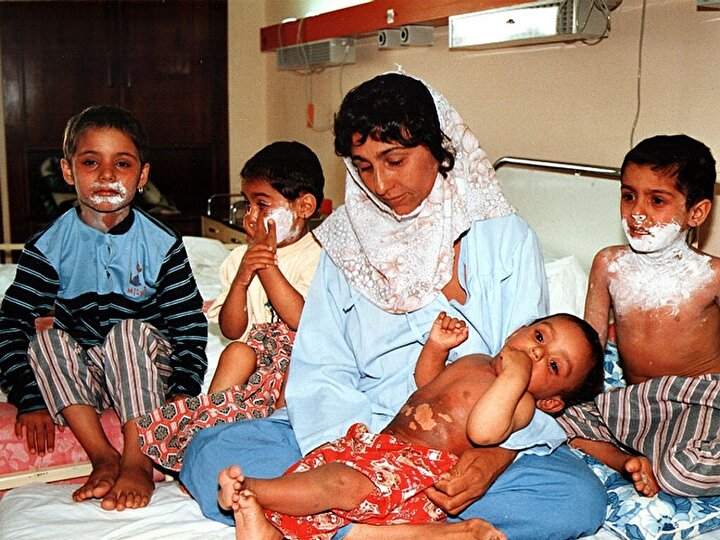

On 10 June 2003, he survived an Israeli assassination attempt (pictured below), which killed two bystanders and left 27 wounded (including one of Rantisi's sons, who was paralyzed). Rantisi himself was wounded by shrapnel in the chest and leg, and he vowed from his hospital bed that Hamas would "not leave one Jew in Palestine." Coming less than a week after the Aqaba summit that launched the Road Map, the attempt on Rantisi's life caused considerable consternation, even from Washington.

Following the attempt on his life, and the assassination of the leading Hamas moderate, Ismail Abu Shanab, Rantisi opposed Qureia's attempts to bring Hamas into a second hudna. And as recently as January 2004, he spoke against Hamas joining a new Egyptian-sponsored ceasefire.

Rantisi was appointed head of Hamas in the Gaza Strip following the assassination of Ahmad Yassin on 22 March 2004. He knew that he was a marked man as soon as he took office, but declined to go underground and was philosophical about the prospect of assassination: It's death whether by killing or by cancer; it's the same thing," he said the day after he was chosen Hamas leader in Gaza. "Nothing will change if it's an Apache (helicopter) or cardiac arrest. But I prefer to be killed by Apache. Rantisi was assassinated in an Israeli helicopter missile strike, as he returned from a clandestine visit to his family on 17 April 2004.