|

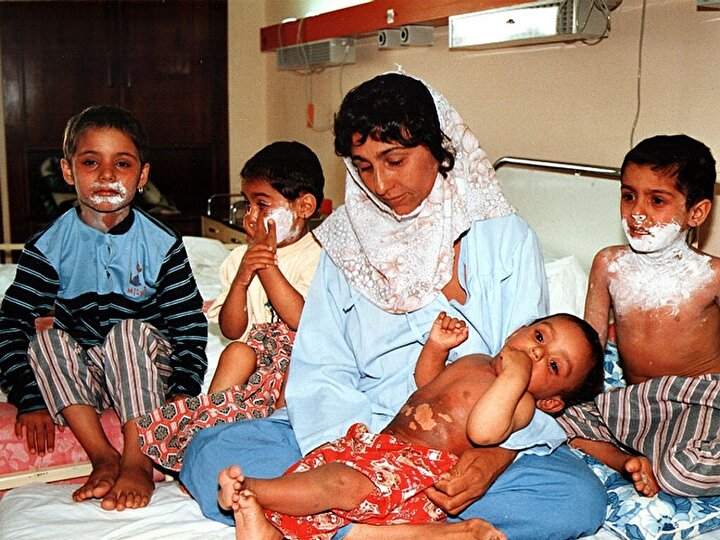

High in remote Kurdish mountains, Iranian villagers still nurse ravaged eyes and lungs, 20 years after Iraqi poison gas attacks that went mostly ignored by world powers then siding with Saddam Hussein against Iran.

It was 4 p.m. on March 17, 1988 when Iraqi planes dropped eight mustard gas bombs over the wood-beamed stone houses of Nowdesheh, nestled in a green horseshoe valley near the border.

"I saw the gas and smelled peaches," said Dara Meshkati, who was 10 years old at the time. "Then my eyes closed and I couldn't see anything. I was blind for two months."

U.N. investigators said 13 people were killed and over 100 injured in the attack -- an event eclipsed by Iraq's chemical assault the day before that killed about 5,000 Iraqi Kurds in Halabja, 25 km across the frontier to the west.

At that time, no asphalt road linked Nowdesheh with the nearest small town of Paveh, so the victims faced a jolting five-hour evacuation over a dirt track through the mountains.

Meshkati, a pale-faced man with listless eyes, recovered his eyesight and is well enough to work in an accountant's office, but still suffers from asthma -- and psychological scars.

"Nobody drinks water from my glasses. People here think I have a problem," he complained.

He is just one of scores of survivors in Nowdesheh, which suffered three gas attacks in the same month of 1988, the final year of Iran's ruinous eight-year war with Saddam's Iraq.

"We went to help the wounded," recalled Rahim Maghrouzi, 52, a surgical mask over his mouth. "We didn't realize it was chemical weapons. My skin turned red. We tried to wash our eyes with water. I still can't breathe properly and I can't work."

Maghrouzi, like many in this village of 5,000, is awaiting the day when Iraqi authorities execute the death sentence passed last year on Ali Hassan al-Majeed, a senior Saddam henchman, for his role in a bloody campaign against Iraqi Kurds in the 1980s.

"Chemical Ali is responsible for what happened to me," said Maghrouzi, using Majeed's nickname. "I hope he is hanged."

Majeed sits on death row in a U.S. jail in Iraq, his fate tangled in a row between the Iraqi government and presidential council over signing off on the execution orders of his cohorts.

Saddam himself was hanged in 2006 on a narrow charge unrelated to his government's actions against Iraqi Kurds and Iran -- something many Iranians view as a missed opportunity.

"We are happy Saddam was put on trial, but sad he was never tried for what he committed against the Iranian people and Kurds in Iraq with chemical weapons," said Shahriar Khateri, a 37-year-old Iranian doctor who runs a support group for survivors -- like himself -- of Iraqi poison gas attacks.

"There was no chance to talk about these atrocities," he told Reuters. "It's the same for Chemical Ali. They should have been tried in an international criminal tribunal."

Khateri said the government had registered at least 55,000 survivors of Iraqi chemical attacks, 7,000 of them civilians, but the true figure was higher because many people exposed to low levels of mustard gas only developed symptoms years later.

Iraq used mustard gas and the nerve agent sarin repeatedly during the war, partly to counter human wave assaults by Iranian basijis -- mostly young volunteers ready to sacrifice themselves for Iran and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's Islamic revolution.

Ali Jalali was a 20-year-old basiji fighting near Merivan, 40 km north of Nowdesheh, in 1987, when an Iraqi rocket filled with mustard gas struck near his tent, killing all but a few of his 24 comrades.

"I thought I would die too," he said.

Jalali, who speaks with a rasping cough, perhaps owes his life to Japanese doctors who later treated him in Tokyo for more than four months for injuries to his eyes, skin and lungs.

Married with one child before the attack, he could have no more children afterwards, but does not regret his sacrifice. "I chose my way myself. I had to do my duty for my country."

Mustard gas commonly inflicts respiratory problems and recurrent lung infections, progressive eye lesions that can lead to blindness, and itching sores and scars on the skin.

In Nowdesheh, Faik Fallahi, a bearded 50-year-old with glasses, sat in his bare living room next to his oxygen bottle and a heap of medicine bottles, capsules and pill packets.

"We have become like laboratory rats," he told visitors on a tour organized to see Chemically Bombarded war zones. "No medicine works for us."

Fallahi, a father of four who is unable to work, said the chemical attack had destroyed his life. "I can't sleep at night. I have no life, no social life. I am at home all the time."

There is no cure for lungs affected by mustard gas, according to Hamid Sohrabpour, a chest specialist who was in charge of Iran's wartime medical response to chemical attacks.

He said Iran had swiftly deployed medical teams, field hospitals and protective clothing once it had identified mustard gas as the cause of the mysterious symptoms of early victims.

"The worst experience was in the first two months. There were loads of patients coming in and it was desperate because we didn't know how to deal with the problem," the physician said.

Sohrabpour, and several survivors insisted that Saddam and Chemical Ali were not the only culprits for the Iraqi poison gas attacks, citing evidence that German and other foreign firms had helped Iraq develop its chemical arsenal.

"Several reports by U.N. experts confirmed the use of nerve agents and mustard gas by Saddam's regime. Unfortunately there was no reaction by the international community," Khateri said.

Source: Information Base of Chemical Weapons Victims |